What is Sarcoma?

What is Sarcoma?

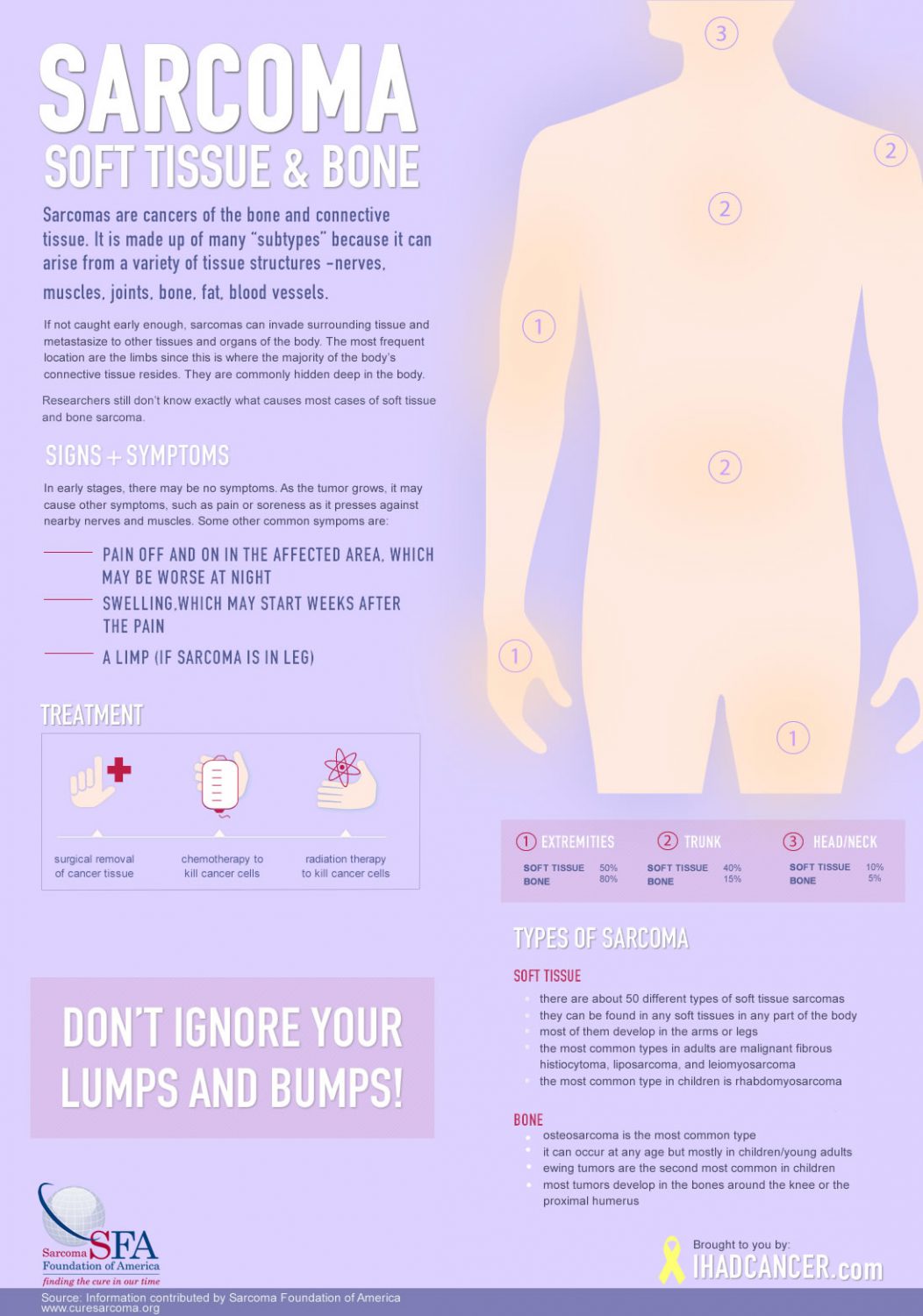

Sarcoma is a rare cancer in adults (1% of all adult cancers), but rather prevalent in children (about 20% of all childhood cancers). It is made up of many “subtypes” because it can arise from a variety of tissue structures (nerves, muscles, joints, bone, fat, blood vessels – collectively referred to as the body’s “connective tissues”). Because these tissues are found everywhere on the body, Sarcomas can arise anywhere. Thus, within each site of the more “common” cancers there is the occasional surprise sarcoma diagnosis (e.g., breast sarcoma, stomach sarcoma, lung sarcoma, ovarian sarcoma, etc.). The most frequent location are the limbs since this is where the majority of the body’s connective tissue resides. They are commonly hidden deep in the body, so sarcoma is often diagnosed when it has already become too large to expect a hope of being cured. Although a lot of the lumps and bumps we get are benign, people should have them looked at by a doctor at an early stage in case it is sarcoma.

Sarcoma is a rare cancer in adults (1% of all adult cancers), but rather prevalent in children (about 20% of all childhood cancers). It is made up of many “subtypes” because it can arise from a variety of tissue structures (nerves, muscles, joints, bone, fat, blood vessels – collectively referred to as the body’s “connective tissues”). Because these tissues are found everywhere on the body, Sarcomas can arise anywhere. Thus, within each site of the more “common” cancers there is the occasional surprise sarcoma diagnosis (e.g., breast sarcoma, stomach sarcoma, lung sarcoma, ovarian sarcoma, etc.). The most frequent location are the limbs since this is where the majority of the body’s connective tissue resides. They are commonly hidden deep in the body, so sarcoma is often diagnosed when it has already become too large to expect a hope of being cured. Although a lot of the lumps and bumps we get are benign, people should have them looked at by a doctor at an early stage in case it is sarcoma.

Sarcoma is sometimes curable by surgery (about 20% of the time), or by surgery with chemotherapy and/or radiation (another 50-55%), but about half the time they are totally resistant to all of these approaches—thus the extreme need for new therapeutic approaches. At any one time, more than 50,000 patients and their families are struggling with sarcoma. More than 16,000 new cases are diagnosed each year and nearly 7,000 people die each year from sarcoma in the United States.

Sarcoma – Cancer of the Connective Tissues

Sarcomas are cancers that arise from the cells that hold the body together. These could be cells related to muscles, nerves, bones, fat, tendons, cartilage, or other forms of “connective tissues.” There are hundreds of different kinds of sarcomas, which come from different kinds of cells.

Dr. George D. Demetri, MD, Director, Sarcoma and Bone Oncology Center, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School

Sarcomas can invade surrounding tissue and can metastasize (spread) to other organs of the body, forming secondary tumors. The cells of secondary tumors are similar to those of the primary (original) cancer. Secondary tumors are referred to as “metastatic sarcoma” because they are part of the same cancer and are not a new disease.

Subtypes

There are two categories of sarcomas:

Soft tissue sarcomas

The term soft tissue refers to tissues that connect, support, or surround other structures and organs of the body. Soft tissue includes muscles, tendons (bands of fiber that connect muscles to bones), fibrous tissues, fat, blood vessels, nerves, and synovial tissues (tissues around joints).

Malignant (cancerous) tumors that develop in soft tissue are called sarcomas, a term that comes from a Greek word meaning “fleshy growth.” There are many different kinds of soft tissue sarcomas. They are grouped together because they share certain microscopic characteristics, produce similar symptoms, and are generally treated in similar ways. (Bone tumors [osteosarcomas] are also called sarcomas, but are in a separate category because they have different clinical and microscopic characteristics and are treated differently.)

Non-soft tissue sarcomas

Non-Soft Tissue Sarcomas – The most common type of bone cancer is osteosarcoma, which develops in new tissue in growing bones. Another type of cancer, chondrosarcoma, arises in cartilage. Evidence suggests that Ewing’s sarcoma, another form of bone cancer, begins in immature nerve tissue in bone marrow. Osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma tend to occur more frequently in children and adolescents, while chondrosarcoma occurs more often in adults.

The Sarcoma Foundation of America has attempted to create location for patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals to quickly learn about a particular sub-type of sarcoma. The number of subtypes of sarcomas is often debated. We have attempted to create a list that encompasses most of the sarcoma subtypes.

We hope this list will be a living document, and we will make every attempt to update it as new treatments and therapies become available for each subtype. Subtypes that cannot be accessed are currently under construction and will have extended information posted shortly. Please check back soon!

Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma (ASPS)

Angiosarcoma

Chondrosarcoma

Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberens

Desmoid Sarcoma

Ewing’s Sarcoma

Fibrosarcoma

Gastrointerstinal Stromal Tumor (GIST)

Non-Uterine Leiomyosarcoma

Uterine Leiomyosarcoma

Liposarcoma

Malignant Fibro Histiocytoma (MFH)

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST)

Osteosarcoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Synovial Sarcoma

Pediatric Sarcoma

Major Types of Soft Tissue Sarcomas in Children |

|||

| Tissue of Origin | Types of Cancer | Usual Location in the Body | Common Ages |

| Muscle | |||

| Striated muscle | Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||

| Embryonal | Head and neck, genitourinary tract | Infant–4 | |

| Alveolar | Arms, legs, head and neck | Infant–19 | |

| Smooth muscle | Leiomyosarcoma | Trunk | 15-19 |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibrosarcoma | Arms and legs | 15-29 |

| Malignant fibrous | Legs | 15–19 | |

| Malignant fibrous | |||

| Fat | Liposarcoma | Arms and legs | 15–19 |

| Blood vessels | Infantile hemangio-pericytoma | Arms, legs, trunk, head, and neck | Infant–4 |

| Synovial tissue (linings of joint cavities, tendon sheaths) | Synovial sarcoma | Legs, arms, and trunk | 15–19 |

| Peripheral nerves | Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (also called neurofibrosarcomas, malignant schwannomas and neurogenic sarcomas) | Arms, legs, and trunk | 15–19 |

| Muscular nerves | Alveolar soft part sarcoma | Arms and legs | Infant-19 |

| Cartilage and bone-forming tissue | Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma | Legs | 10–14 |

| Extraskeletal mesenchymal | Legs | 10–14 | |

Possible Causes

Scientists do not fully understand why some people develop sarcomas while the vast majority do not. However, by identifying common characteristics in groups with unusually high occurrence rates, researchers have been able to single out some factors that may play a role in causing sarcomas.

Studies suggest that workers who are exposed to phenoxyacetic acid in herbicides and chlorophenols in wood preservatives may have an increased risk of developing sarcomas. An unusual percentage of patients with a rare blood vessel tumor, angiosarcoma of the liver, for example, have been exposed to vinyl chloride in their work. This substance is used in the manufacture of certain plastics.

In the early 1900s, when scientists were just discovering the potential uses of radiation to treat disease, little was known about safe dosage levels and precise methods of delivery. At that time, radiation was used to treat a variety of noncancerous medical problems, including enlargement of the tonsils, adenoids, and thymus gland. Later, researchers found that high doses of radiation caused sarcomas in some patients. Because of this risk, radiation treatment for cancer is now planned to ensure that the maximum dosage of radiation is delivered to diseased tissue while surrounding healthy tissue is protected as much as possible.

Studies have focused on genetic alterations that may lead to the development of sarcomas. Scientists have also found a small number of families in which more than one member in the same generation has developed sarcoma. There have also been reports of a few families in which relatives of children with sarcoma have developed other forms of cancer at an unusually high rate. Sarcomas in these family clusters, which represent a very small fraction of all cases, may be related to a rare inherited genetic alteration. However, in the vast majority of cases, sarcoma is a completely random event in a family’s cancer history.

Certain inherited diseases are associated with an increased risk of developing soft tissue sarcomas. For example, people with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (associated with alterations in the p53 gene) or von Recklinghausen’s disease (also called neurofibromatosis, and associated with alterations in the NF1 gene) are at an increased risk of developing soft tissue sarcomas.

How is Sarcoma Diagnosed?

The only reliable way to determine whether a tumor is benign or malignant is through a surgical biopsy. Therefore, all soft tissue and bone lumps that persist or grow should be biopsied. During this procedure, a doctor makes an incision or uses a special needle to remove a sample of tumor tissue. A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope. If cancer is present, the pathologist can usually determine the type of cancer and its grade. The grade of the tumor is determined by how abnormal the cancer cells appear when examined under a microscope. The grade predicts the probable growth rate of the tumor and its tendency to spread. Low-grade sarcomas, although cancerous, are unlikely to metastasize. High-grade sarcomas are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Sarcoma Treatment

In general, treatment for sarcomas depends on the stage of the cancer. The stage of the sarcoma is based on the size and grade of the tumor, and whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or other parts of the body (metastasized). Treatment options for sarcomas include surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

Surgery is the most common treatment for sarcomas. If possible, the doctor may remove the cancer and a safe margin of the healthy tissue around it. Depending on the size and location of the sarcoma, it may occasionally be necessary to remove all or part of an arm or leg (amputation). However, the need for amputation rarely arises; no more than 10 percent to 15 percent of individuals with sarcoma undergo amputation. In most cases, limb-sparing surgery is an option to avoid amputating the arm or leg. In limb-sparing surgery, as much of the tumor is removed as possible, and radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy are given either before the surgery to shrink the tumor or after surgery to kill the remaining cancer cells.

Radiation therapy (treatment with high-dose x-rays) may be used either before surgery to shrink tumors or after surgery to kill any cancer cells that may have been left behind.

Chemotherapy (treatment with anticancer drugs) may be used with radiation therapy either before or after surgery to try to shrink the tumor or kill any remaining cancer cells. If the cancer has spread to other areas of the body, chemotherapy may be used to shrink tumors and reduce the pain and discomfort they cause, but is unlikely to eradicate the disease. The use of chemotherapy to prevent the spread of sarcomas has not been proven to be effective. Patients with sarcomas usually receive chemotherapy intravenously (injected into a blood vessel).

Doctors are conducting clinical trials in the hope of finding new, more effective treatments for sarcomas, and better ways to use current treatments.

Click here for a list of medical centers and hospitals specializing in sarcoma. While the list is not comprehensive, it includes the leaders in sarcoma research and treatment. Because sarcomas are rare, it is important to find physicians and multidisciplinary treatment centers that have experience with this disease.

Click here for list of Clinical Trials that may be helpful.